Guest blog by Maddy Diment, Geography graduate from the University of Oxford

In the summer of 2019, Maddy completed her dissertation research on the roles that food-sharing apps play in reducing food waste in Oxford. Read on to learn more about her research and what she found out, including who uses food-sharing apps and why, whether they are a useful part of the solution to our food waste problem, and what we can learn for communicating the problem of food waste.

How much food we waste

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), one-third of all food produced globally goes to waste. Significantly, for most high-income countries, over 70% of all food waste takes place in the home (WRAP, 2021). This level of inefficiency in the global food system has significant implications; if it were a country, food waste would be the third-largest emitter of green-house gases (FAO, 2015). Although food waste is not a new problem, it has recently been reconsidered within the context of the ‘digital age’, and therefore, novel technological solutions have also come to the fore. Food-sharing apps, defined as online platforms that save and distribute surplus food, present themselves as the next step in this direction.

Research methods and key findings

In the summer of 2019, I interviewed 39 people, many of whom lived in Oxford, to ask them questions about their own food consumption and waste habits, as well as their experiences using two food-sharing apps. I also spent some time volunteering as a Food Waste Ambassador at Hogacre Cafe, organising and hosting workshops to engage families and young people in discussions around food waste (see picture below). I also volunteered for one of the food-sharing apps studied, collecting surplus food from cafes across Oxford and distributing the products via the app.

What are food-sharing apps?

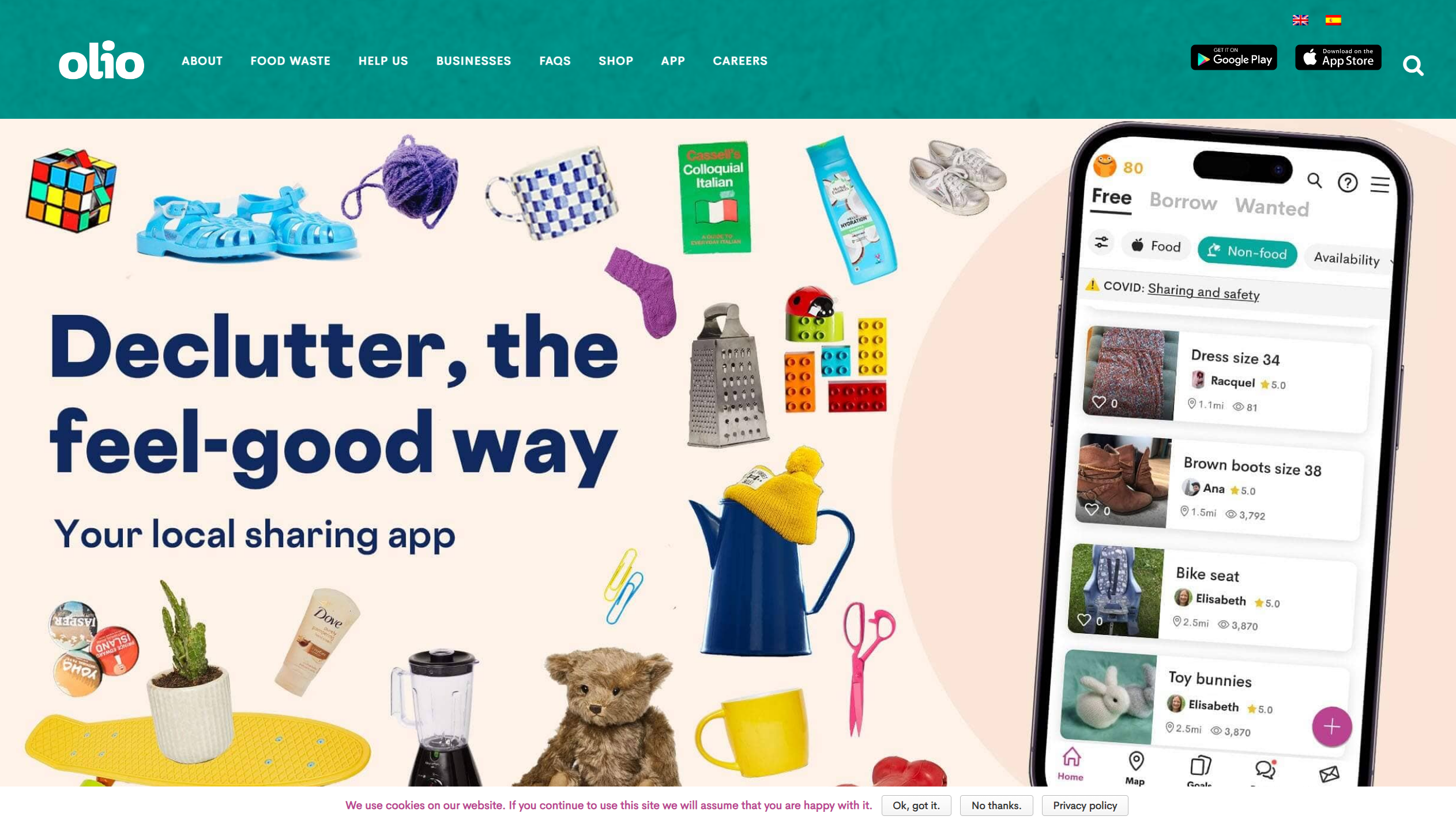

There are two broad models of food-sharing app. You can think of the first like Gumtree - users upload stuff (in this case, food) they don't want, and share it for free with neighbours in their vicinity. The second type is more like a an outlet store – brands sell items (in this case, food) that are not wanted/ about to go off for a reduced price. Both apps claim to help reduce food waste.

Here are five key insights from my research:

1. Who uses food-sharing apps?

Mostly young people (18-30 yrs)

Most app users identified as female

2. What motivates people using the apps?

To get a bargain and save money – this consistently ranked as the #1 reason

To reduce food waste – motivated by ethical and economic reasons

To help local businesses – to reduce their waste and to support them financially

To meet new people in the area. Participants, overall, felt that food-sharing apps contributed something positive to the Oxford community and helped to build on existing relationships between neighbours.

3. What stops people from using the apps?

Many participants felt that a lack of time was a large barrier to entry for using food-sharing apps as it involves thinking about and finding domestic surplus food, taking pictures of the food, uploading the picture to the app and writing the associated health and safety information, and coordinating the exchange of the food with another app user.

Many participants noted that a lack of money may also be a barrier to entry as certain food-sharing apps require users to purchase the surplus food advertised on the app (albeit for a reduced cost).

A few participants mentioned that food-sharing apps seemed like a ‘middle class’ thing to have and engage with and therefore, felt less willing to participate.

4. How do the apps communicate the issue of food waste?

Many participants noted a difference in language (i.e. food waste vs surplus food) in the marketing of food-sharing apps. Participants regarded the term ‘food waste’ as being less desirable and less valuable (socially as well as monetarily) than the term ‘surplus food’.

5. Who should be responsible for managing food waste?

Many participants felt that individuals now shield the burden of responsibility regarding managing food waste. They felt that food sharing apps perpetuated this shifting role of governance.

Participants felt that the local council and national government could do more to engage individuals, companies and institutions in improving food waste systems and to prevent food waste altogether.

Nearly all participants argued that a combination of different strategies and actors, operating at multiple scales, is required in order to reduce future food waste in Oxford.

Food-sharing apps are a part of the solution

Food-sharing apps can be considered as part of the solution in achieving low levels of food waste, however, they are no silver bullet.

Food-sharing apps have increased awareness about food waste and have clearly demonstrated the positive impacts and rewards of reducing food waste.

We should continue to raise awareness about food waste offline as well as online – both are required to create and sustain systemic change.

OLIO, an app that encourages peer-to-peer food-sharing

Too Good to Go, an app that offers discounted food from retailers and brands to reduce their food waste

If you would like to learn more about my dissertation, or ask any questions about how you can reduce your food waste in Oxford, please feel free to contact me at maddydiment@hotmail.com. You can also find me on LinkedIn.