If you are noticing that an idea in your organisation or network isn’t working out, it may be worth taking a step back to be curious about it. Do the practitioners feel empowered to act? Is it important enough to pursue? Do they have enough time, money, or support to get it done?

Local food systems are characterised by their focus on localised production, distribution, and consumption of food, as well as many shared aspirations, values, and experiences. They are often seen as a way to improve food security, build local economies, and protect the environment.

Local food systems are always in some sort of flux, with new entrants to the system, new policies and regulations, changes to what people want or need, funding availability, etc. Covid-19 was a great example of change to the local food system, with runs on things at supermarkets, increased demand for local produce and deliveries, and people looking for volunteer work to get them out of the house.

Big and little changes require practitioners to self-organise. They do this regularly, from the day-to-day activities what time to have a meeting, to big, important things, like applying for grants or starting new projects. Local food practitioners do, and re-do, and make do. They plan and implement, they fail and try again. They work with people in their groups or organisations, with other people in other groups and organisations, and with pretty much anyone who might have a passing interest or skill in food.

Self-organisation is a strange concept. On the surface, it’s one of those things you hear, and you think, yeah, that makes sense. Once you dig into the academic research, though, it’s a minefield of misunderstandings and appropriation.

Self-organisation is a process where people work together in collective action, problem-solving, and consensus-building to achieve their goals. The idea stems from complexity theory, and describes chemical and physical interactions, which were later applied to economics, computing, and social domains. The classic example of self-organisation is people spontaneously coming together to help out following a natural disaster.

Self-organisation can be a powerful process, but there are potential problems. It can be used to reinforce injustice, stigmatisation, and patchy servicing. For example, when social support is withdrawn (think: austerity), community groups will often coalesce to fill the gap. This allows those in power to point and say, ‘Hey look, they didn’t need us after all.’ This leads to self-exploitation of volunteers and community leaders, and to neglect of those who were unable to self-organise new systems.

Although there are some drawbacks to self-organisation, it isn’t avoidable, nor should it be avoided. It is a natural response to disruptions like Covid-19, political unrest, and climate change events. We need to engage with it in order to fully understand how and why self-organisation happens, and how to ensure it is effectively and fairly enacted.

This research was done in Oxford, in the UK, and in Freiburg im Breisgau, in Germany. It was based on their respective local/regional food systems, which gave a really good picture of self-organisation in their communities during turbulent times.

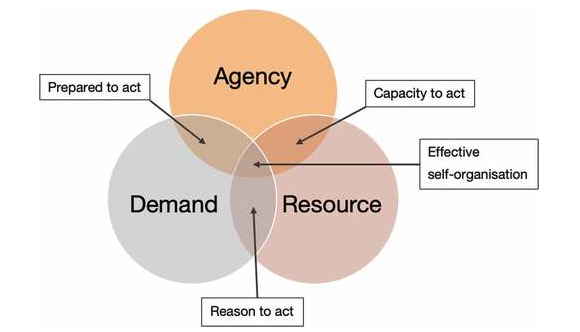

What the research showed was that effective self-organisation – that is, ideas that can transition from thought into action – relied on three things. These are agency, demand, and resource.

Agency is the capacity people have to make and enact decisions, which are shaped by personal beliefs, motivations, and values. This can empower people to take action, have difficult discussions, build networks, engage with authorities, and manage complex governance structures. A lack of agency can disproportionately impact marginalized communities, newcomers to the field, and those who aren’t invested in the process or outcomes. Agency doesn’t happen in a vacuum – it is nurtured through capacity building and social learning.

Demand is implied, but rarely explicitly explored. It is demand that drives community to take action, sometimes due to crisis, sometimes due to simple, everyday needs. Demand-driven self-organisation can be seen when community members create new food projects, engage in policymaking, or put pressure on practitioners for things like decreased plastic use or increased organic production.

Resource is often discussed in relation to self-organisation in terms of time, money, energy, relationships, physical space, and institutional and public support. Resourcing can be a limiting or enabling factor, and these different forms often feed into each other. Limits on any of them can impact the success of an organisation. Time is particularly important, because local food systems rely heavily on donated time from both volunteers and staff. This can leave local food systems unevenly distributed, because it relies on those with the luxury time to give. A lack of resource can also impact innovation and experimentation – without enough slack the capacity to self-organise is compromised.

When these three elements overlap in part, there may get preparedness to act, capacity to act, or reasons to act, but unless they come together in harmony, it is difficult to achieve effective self-organisation. It takes all three for that to happen. Local food systems are complex, constantly evolving, and regularly under pressure. But by better understanding self-organisation, which local food practitioners rely on heavily, we can better support the development and resilience of local food systems.

Interested in reading more? You can access the original paper here: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21683565.2023.2180565 (it’s open access!)

Emma Burnett is a doctoral researcher at the Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience and sits on GFO's steering committee. She researches competition, cooperation, and self-organisation in local food systems, and has been involved in Oxfordshire's food scene for over a decade. You can find more of her work here.